America’s thirst for oil is as strong as ever. And thanks to a giant boom in North Dakota, more U.S. oil is extracted at home.

That’s turned some cattle ranchers into millionaires, a few oil bosses into billionaires and put money in the pockets of working people.

But those riches have come at a price.

“What’s the most dangerous job in America? ... I’d have to say oilfield worker.”

— Curtis Hanzel, Killdeer Area Ambulance

As North Dakota’s oil boom exploded with drilling rigs, frac crews and oilfield workers, on-the-job deaths jumped to record highs.

Since 2008, more than 50 men have died at oilfield sites in this western state. Dozens more have perished on construction sites and narrow, two-lane highways filled with big rigs.

Before the oil boom, rural ambulances rarely ventured out of garages. Then oil rigs, trucks and big equipment arrived, and emergency calls spiked. So did hospital admissions.

Since 2008, the number of people treated for traumatic injuries at local hospitals has doubled.

Source: North Dakota Department of Health.

“North Dakota continues to stand out as an exceptionally dangerous and deadly place to work.”

— AFL-CIO report

Government accounts of fatal accidents make for grim reading.

There are reports of oilfield workers falling to their deaths, suffering deadly burns, getting struck with giant pipes, suffocating from poisonous gases and being crushed by heavy equipment.

And no place is more dangerous to work than North Dakota. A 2015 AFL-CIO report listed North Dakota’s on-the-job death rate at 14.9 people per 100,000 workers, higher than any other state for the third year in a row.

“Among all states North Dakota continues to stand out as an exceptionally dangerous and deadly place to work,” the report reads.

Now isolate those jobs for the mining, oil and natural gas sector. The hazards of working in North Dakota’s oilfields trump those of all other states, including Texas, Louisiana and Oklahoma.

North Dakota’s fatality rate in the mining, oil and gas extraction sector is almost seven times the national average, according to an analysis of government data (84.7 per 100,000 workers vs. 12.4 per 100,000 workers). And most of those deaths happened in North Dakota’s oilfields.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

“I met this guy tonight and I’m going to marry him.”

— Lacey Breding

They met at a rodeo. She was there because she had nothing else to do. And then she saw a cute guy with unruly brown hair tucked under his cowboy hat.

“I knew his friends, but I’d never had seen him before,” Lacey Breding says.

His name was Dustin Bergsing.

“With that excessive gas … Katy bar the doors, man. You’re dead.”

— Mr. X, Former Marathon Oil Employee

Dustin Bergsing rode broncos. He raced motocross. He was a strapping 21-year-old Montana man with a shit-eating grin who did what Montana men do.

As oil field jobs go, though, Dustin had a pretty safe one. He wasn’t swinging pipes on a drilling rig or working near big, moving trucks.

Instead, he made his living peeking inside giant oil tanks. Dustin was a well watcher.

One bitter cold night, something went very wrong.

A plume of gas vapor enveloped him. Dustin was found slumped, sitting on a catwalk, near the tanks he was assigned to monitor. Under his insulated coveralls, facemask and black work boots, he was wearing green checkered wooly pajamas.

Dustin was the first of several workers to die from inhaling volatile organic compounds at well sites in North Dakota and Montana. At the time of his death, he was working at a well site owned by Marathon Oil near Mandaree, North Dakota.

“They told me I couldn’t write any more emails … because lawyers could discover it.”

— Mr. X, Marathon Oil Whistleblower

Did Dustin Bergsing die unnecessarily? A former Marathon Oil employee thinks so.

In this interactive timeline, read and listen to events related to Dustin Bergsing’s life and death. The timeline includes audio testimony from Mr. X, a Marathon Oil whistleblower who alleges the company ignored safety warnings that may have prevented Dustin’s death. The words of Mr. X are excerpts from a sworn statement he gave to Minneapolis attorney Fred Bremseth on August 25, 2012. Bremseth represented Trista F. Juhnke, Dustin’s mother, in a wrongful death lawsuit against Marathon Oil.

We hired an actor to read excerpts from that document, which has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Dustin Bergsing is born.

Dustin meets Lacey Breding at the Northern Rodeo Association finals in Billings, Montana.

Although separated by 106 miles of Montana highway (he lives in Livingston, she’s in Edgar), Dustin and Lacey see each other whenever possible.

On her birthday, Lacey discovers she’s pregnant.

Dustin and Lacey move in together in Edgar, Montana.

Dustin begins work at Across Big Sky Flow Testing, a company performing oilfield services for Marathon Oil in North Dakota.

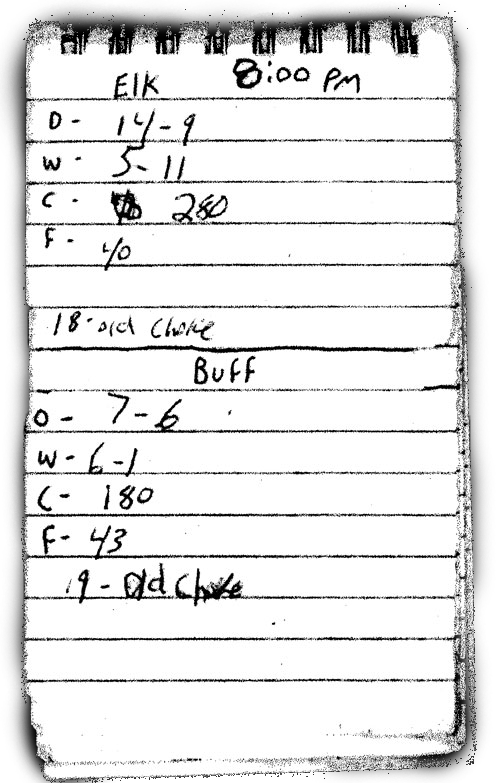

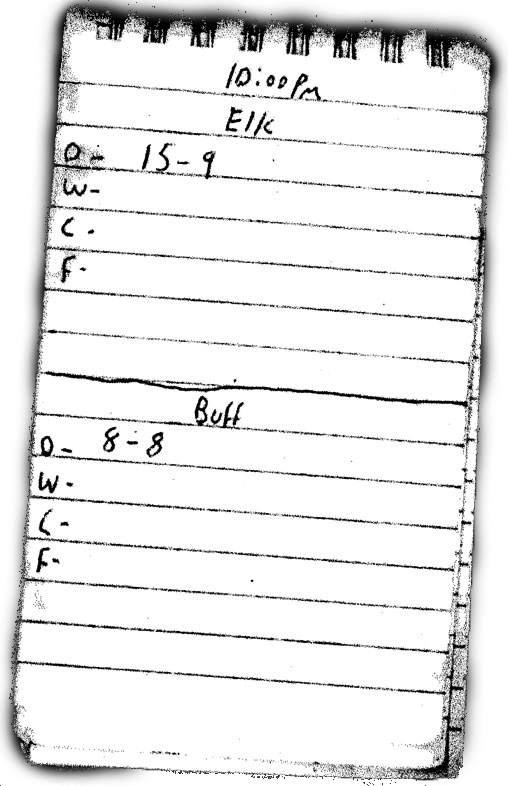

Buffalo and Elk Creek wells near Mandaree, North Dakota — and owned by Marathon Oil — begin producing crude oil and gas. Mr. X, a former Marathon Oil engineer, describes the process.

Mr. X begins work at Marathon Oil in North Dakota.

Mr. X questions safety issues at Marathon Oil well sites in North Dakota. “There’s 15 to 20 e-mails in regards to, ah, poor design,” he says.

Dustin and Lacey make plans to marry on June 30, 2012.

Dustin becomes a father when Lacey gives birth to McKinley Faith Bergsing, a girl. Lacey says he was a really good Dad.

Marathon Oil boss tell Mr. X to stop writing e-mails warning of safety issues: “If you write any more of those, I’m gonna have to fire you.”

Dustin, Lacey and friends celebrate New Year’s Eve.

Dustin and Lacey apply for a home mortgage loan.

Dustin, age 21, dies at well site owned by Marathon Oil in North Dakota. Mr. X describes how he learned of Dustin's death.

That afternoon, Lacey learns the couple is approved for a mortgage.

North Dakota Medical Examiner’s office performs autopsy on Dustin Bergsing to determine cause of death.

Occupational Safety and Health Administration begins investigation into Dustin Bergsing’s death.

Dustin would have celebrated his 22nd birthday.

An OSHA official sends condolence letter to Dustin Bergsing’s family.

An OSHA official sends condolence letter to Dustin Bergsing’s family, writing “please accept my sincere sympathy and regret for your loss.”

Read the Letter“Worker safety is all too often left out when an industry or technology grows rapidly.” — OSHA administrator admission in a draft of letter to President Obama’s chief domestic policy advisor. The letter was obtained by Black Gold Boom during a Freedom of Information Act request.

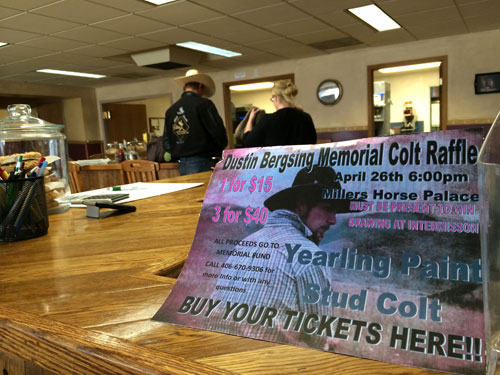

Friends organize the Dustin Bergsing Memorial Bullride in Laurel, Montana. Watch the video in Chapter 7 to see more.

Another oilfield worker nearly dies under similar circumstances. Listen to Mr. X’s description of the event. (Note: An IR camera is an infrared camera. LEL is lower explosive limit. VOC is volatile organic compound.)

Marathon Oil fires Mr. X for “performance reasons,” according to an email from a company spokesman. Mr. X says he was fired for being a whistleblower.

OSHA writes a letter to Dustin Bergsing’s family saying its investigation “found that no alleged violation(s) of safety and health standards had occurred related to the accident, and therefore, no citations or proposed penalties were issued to the employer.” Black Gold Boom obtained a copy of the OSHA investigation, which focused on whether Dustin died of hydrogen sulfide gas, an odorless, colorless gas that some wells naturally produces. The gas, which is also known as H2S, is deadly. A test of Dustin’s H2S monitor after his death showed no exposure to H2S, hence the lack of an OSHA fine.

The North Dakota Medical Examiner’s Office issues report on Dustin’s death.

Postmortem examination revealed … multiple hydrocarbon compounds, components of petroleum, in both the blood and in the lungs. No other drugs or toxic substances were found. Death is the result of the decedent’s inhaling vapors from petroleum.

Dr. William Massello III

Dustin and Lacey would have married.

Dustin’s mother, Trista F. Juhnke, sues Marathon Oil, alleging the Houston-based company was “negligent in its specifications, inspections, and maintenance of the oil well, equipment and tank in the vicinity of the site of death of Dustin Bergsing.”

Read the Court DocumentMarathon Oil disputes many of the allegations in Trista F. Juhnke’s lawsuit.

Read the Court DocumentMr. X. gives a sworn statement to an attorney alleging Marathon Oil ignored safety warnings at North Dakota well sites.

Juhnke v. Marathon lawsuit settled out of court for an undisclosed amount of money. Attorney Fred Bremseth later described the sum as “very substantial.”

Marathon Oil uploads “Marathon Oil Safety” video to YouTube. “Everybody goes home today,” says Whitney Schaper, a Marathon reliability engineer. “Not just Marathon employees, but also our contractors.”

(Shortly after this interactive debuted, Marathon Oil hid its safety video from the viewing public.)

Black Gold Boom airs four-part series on oilfield worker safety in North Dakota, including details of the death of Dustin Bergsing and the allegations of wrongdoing by Mr. X, the former Marathon Oil environmental engineer.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), a division of the Centers of Disease Control, reports: “At least four workers [including Dustin Bergsing] have died since 2010 in what appears to be acute chemical exposures during flowback operations at well sites in the Williston Basin (North Dakota and Montana).”

Read the ReportNIOSH evaluates levels for the cancer-causing agent benzene for well site workers like Dustin Bergsing. Of the 17 workers sampled, 15 reported higher levels of benzene than the agency recommends for humans.

Read the StudyReporter Mike Soraghan of EnergyWire reports on the four men, including Dustin Bergsing, who died of hydrocarbon poisoning in North Dakota and Montana. “The documents show striking similarities between the four cases,” Soraghan writes.

“Marathon Oil is saddened by the loss of Dustin Bergsing.”

— Marathon Oil statement

Marathon Oil, a Houston-based company with nearly $11 billion in annual revenue, refused to be interviewed about the case or Mr. X’s testimony. Instead, the company issued this statement:

“Marathon Oil is saddened by the loss of Dustin Bergsing, a contractor working on one of our locations in the Bakken field in January 2012. The loss of Dustin is tragic — for his family, friends and co-workers. Everyone within the Marathon Oil family takes this event serious, and none more so than our Bakken asset team. No injury or loss of life is acceptable.”

Regarding Mr. X, Marathon says he was fired for “performance reasons” and that his sworn statement is “grossly inaccurate and wholly without merit.” The company says Mr. X’s statement happened without its lawyers in the room and therefore, it’s one-sided.

Fred Bremseth, the attorney representing Bergsing’s family, disagrees. “The court process certainly would allow Marathon Oil to take a comprehensive discovery deposition as part of the normal pre-trial procedures,” Bremseth says. “They could have done that if they wanted to.”

Marathon Oil eventually reached an out-of-court settlement with Dustin Bergsing’s family for an undisclosed sum of money.

“He’s that one person you could always be around, no matter what.”

— A friend mourning the loss of Dustin Bergsing

Jason Bold and Dustin Bergsing liked to drink beer together, tease their girlfriends and talk about all kinds of things. They’d both competed in rodeos and spent time working in North Dakota’s oilfields.

After Dustin’s death from hydrocarbon poisoning on a well site, Jason organized the Dustin Bergsing Memorial Bullride in Laurel, Montana.

And he’s a father now, just like Dustin was at the time of his death.

Performed by Charlie Parr Traditional arrangement by Charlie Parr From the album ‘Keep Your Hands On The Plow’

Courtesy of Little Judges Music, by exclusive arrangement with Heyday Media Group. charlieparr.com

Written & performed by Geir Jenssen Published by Touch Music biosphere.no

Black Gold Boom: Oil to Die For is a co-production of 2 below zero, Independent Television Service (ITVS), Prairie Public Broadcasting and the Association for Independents in Radio (AIR), in association with Localore, with funding provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB).

More From

Black Gold Boom

Black Gold BoomTelevision Documentary

Rough Ride

Rough RideInteractive Documentary

Highway of Hope

Highway of HopeRadio Portrait